Trending

“Urban Doom Loop” of Vacant Offices: How Far Will It Go?

Even the mainstream is starting to acknowledge the massive problem of vacant office buildings littering American cities, slowly turning them into post-Covid wastelands.

While a few pundits are claiming (in somewhat Orwellian fashion) that the surge in empty commercial real estate is actually a chance for a utopian turnaround in the ashes of Covid weirdness, the potential for an “Urban Doop Loop” triggered by CRE is now being widely acknowledged as a possible trigger for a broader economic meltdown.

Learn more:

Economist Warns Rollout Of The Mark Of The Beast Being Prepared By Central Bank

With a pre-existing problem amplified drastically by COVID-19 and then set in stone, the rising office vacancy rate has no real solution. The problem is slowly and steadily getting worse, becoming a “new normal” that simply can’t go on forever without further economic repercussions. And this time is distinct from other major downturns in that during previous shocks, like 9/11 and the 2008 financial crisis, everyone more or less agreed that eventually, things would pick back up again. This time, it’s permanent.

Take just a few examples:

New York — There’s a new record for office vacancies in Manhattan, which have risen above 17%, and show no signs of slowing down. Vacancies have grown 70% in Manhattan since Covid (growing 20% nationally in the same period), with the Financial District hardest hit.

Pittsburgh — Currently sitting above 20% vacant, or 27% if you factor in subleases, it’s estimated thatnearly half of the city’s commercial real estate could be empty within four years. If not reversed, a local crisis (at the very least) seems all but assured.

Portland — With the highest office vacancy rate in the nation — a mind-melting 30% or more — Portland officials are offering desperate pleas in the form of tax credits and other incentives to fill its deserted commercial buildings.

Los Angeles — Demand is so low for commercial real estate that, in one case, developers abandoned plans to build a shiny new 61-story office tower in place of an empty commercial building. Instead, they demolished it and installed a handful of EV charging stations.

There’s no great solution. Most cities are floating quixotic proposals to turn empty offices into apartments to “fix” the crisis, but this is often too expensive to be practical and requires navigating lots of bureaucratic red tape, like changes to zoning laws.

Recognizing how dependent their cities are on property taxes harvested from commercial real estate, getting municipal governments to change zoning laws actually might be the easiest part. Vacant office buildings equate to plummeting revenue, forcing cities to make up the loss by increasing taxes elsewhere or reducing spending.

For one, New York City’s commercial real estate accounts for 20% of the property tax and 10% of overall revenue, with the city comptroller projecting a $1.1 billion shortfall from vacant offices in 2024. In Boston, property taxes on office buildings comprise a staggering 22% of total revenue.

Even the most optimistic, desperately trying to see this crisis as an “opportunity” to start fresh, are being forced to acknowledge the challenges. But turning commercial spaces into residential ones and hoping for the best is one of the only few “Hail Mary” options cities have left to avoid a further implosion that bleeds into the banking sector and sets off a chain reaction.

For the hopeful, such as Dana Lind of the Penn Institute for Urban Research, the buyer’s market in big cities provides a golden opportunity that was missed during the 2008 crisis. She hopes local buyers will use these empty buildings to invigorate cities by serving local needs, or that the empty offices will be bought by cities themselves and turned into vibrant community centers:

“Smart investors see what is happening in American downtowns four years out from the onset of the pandemic—the business fundamentals of cities like New York, Boston, or Houston are relatively stable and could even dramatically improve. Why not buy?”

Sure, fundamentals could improve. But will they? She goes on to say:

“As commercial properties fall into foreclosure in 2024, cities could take steps to better shape the city they want in the future by actually investing in those properties themselves.”

It all sounds lovely. Unfortunately, I’m less confident the CRE crisis can be contained this way, and that it won’t contribute to a broader meltdown.

Empty offices mean fewer people visiting the surrounding stores and restaurants. As the economic damage begins to snowball, the domino effect eventually reaches the banking sector, especially smaller and mid-size banks — and thus, the “Doom Loop” takes form. If we are to take the recent failure of regional firms like New York Community Bancorp as evidence, this vicious spiral may already be beginning.

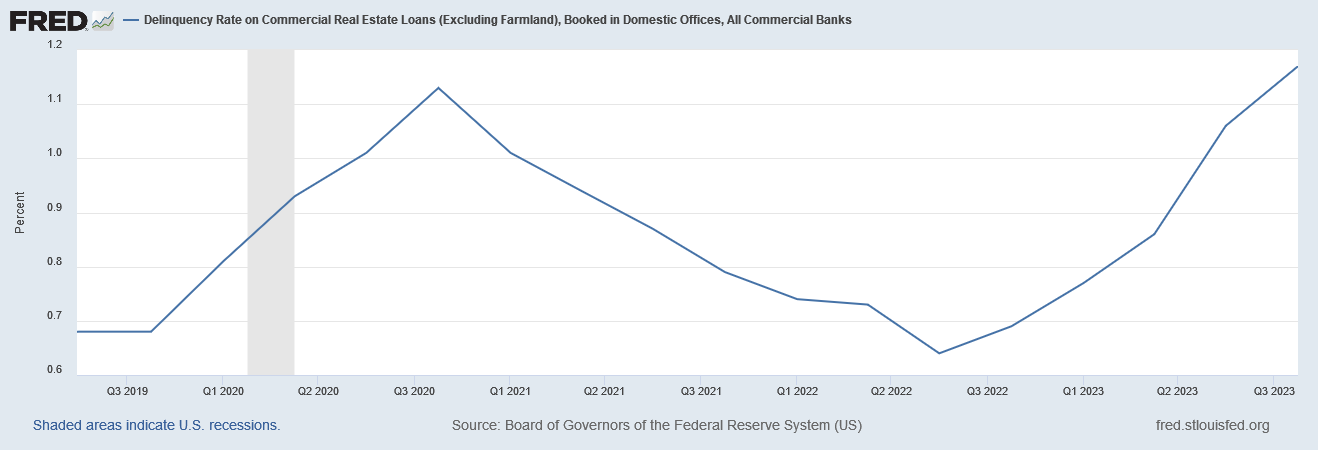

CBS reported in January that office loan delinquencies were up a shocking four times compared to the previous year. In under two years, commercial real estate loans totaling $1.5 trillion are due to expire, portending disaster for the economy when the bill comes due and office owners can’t pay it. According to data from the St. Louis Fed, delinquency rates on commercial real estate loans have already ticked above their Covid peak:

Occupancy Rate on CRE Loans (Excluding Farmland), Booked in Domestic Offices, Q3 2019 to Q3 2023

In an industry that lives and dies by interest rates, the problem provides another powerful source of pressure on the Fed to cut rates this year, boosting the bottom line for commercial landlords and developers who are being squeezed by a high cost of borrowing and already scrambling to change the terms of their debt.

A recent Moody’s podcast offers a glimmer of hope that there are enough factors to offset the challenges of CRE delinquencies. But with the rate cuts that the market hoped for last year now expected to be much less significant, will put further stress on a CRE market that’s addicted to rock-bottom borrowing costs. If the Fed cuts rates too low, inflation will spiral out of control, but keep them too high, and other things (like CRE) will continue to bend and break.

Learn Why The Globalists Are Killing Their Own Monetary System

Read the full article here