Top News

Comedian’s stories of victimization are mostly made up

Have your heard of Hasan Minhaj? I have, though I can honestly say I’ve never watched a minute of one of his stand-up specials. He also had a Jon Stewart/Samantha Bee style cable show called “Patriot Act” in which he tried to make news topics into amusing entertainment. That show ran from 2018 to 2020. Despite the short run, the show was broken up into 6 seasons of 6-8 shows each. The show won both an Emmy and a Peabody award.

Today the New Yorker published a story about Minhaj which makes the case that a number of the stories he tells in his act, stories which he presents as true, are actually at least partly made up. Minhaj claims his goal in some cases was to tell an “emotional truth.” even if it wasn’t the actual truth.

In Minhaj’s approach to comedy, he leans heavily on his own experience as an Asian American and Muslim American, telling harrowing stories of law enforcement entrapment and personal threats. For many of his fans, he has become an avatar for the power of representation in entertainment. But, after many weeks of trying, I had been unable to confirm some of the stories that he had told onstage. When we met on a recent afternoon, at a comedy club in the West Village, Minhaj acknowledged, for the first time, that many of the anecdotes he related in his Netflix specials were untrue. Still, he said that he stood by his work. “Every story in my style is built around a seed of truth,” he said. “My comedy Arnold Palmer is seventy per cent emotional truth—this happened—and then thirty per cent hyperbole, exaggeration, fiction.”

In Minhaj’s 2022 Netflix standup special, “The King’s Jester”—a biographical reflection on fame, vainglory, and Minhaj’s obsession with social-media clout—he relays a story about an F.B.I. informant who infiltrated his family’s Sacramento-area mosque, in 2002, when Minhaj was a junior in high school. As Minhaj tells it, Brother Eric, a muscle-bound white man who said he was a convert to Islam, gained the trust of the mosque community. He went to dinner at Minhaj’s house, and even offered to teach weight training to the community’s teen-age boys. But Minhaj had Brother Eric pegged from the beginning. Eventually, Brother Eric tried to entice the boys into talking about jihad. Minhaj decided to mess with Brother Eric, telling him that he wanted to get his pilot’s license. Soon, the police were on the scene, slamming Minhaj against the hood of a car. Years later, while watching the news with his father, Minhaj saw a story about Craig Monteilh, who assumed the cover of a personal trainer when he became an F.B.I. informant in Muslim communities in Southern California. “Well, well, well, Papa, look who it is,” Minhaj recalls telling his father. “It’s our good friend Brother Eric.”

Onstage, a large screen behind Minhaj flashes news footage from an Al Jazeera English report on Monteilh. Minhaj’s teen-age hunch, it seems, was proved right. The moment is played for laughs, but the story underscores the threat that being Muslim in the United States carried during the early days of the war on terror.

Only none of that really happened. There was a Brother Eric but he was in prison in 2002. He did later work for the FBI but in southern California. He was never in Sacramento and Minhaj never met him.

Minhaj also tells a story in one of his comedy specials about the strong negative reaction some of his stories on Patriot Act generated. He claims someone sent a letter to his home which was full of white powder and that some of the powder got on his daughter who had to be rushed to the hospital. But again, that never happened and in an interview Minhaj admitted it never happened. Instead, he claimed there really was a package with some white powder which he opened at home but, apart from making a joke to his wife, he never told anyone about it at the time.

Minhaj insisted that, though both stories were made up, they were based on “emotional truth.” The broader points he was trying to make justified concocting stories in which to deliver them. “The punch line is worth the fictionalized premise,” he said.

Did the revised story leaving his daughter out of it really happen? There’s no proof it did. Another example from earlier in his career:

The central story of his first Netflix special, “Homecoming King,” which was released in 2017, is about his crush on a friend, a white girl with whom he shared a stolen kiss and who accepted his invitation to prom but later reneged in a humiliating fashion; Minhaj showed up on her doorstep the night of the dance, only to see another boy putting a corsage on her wrist. Onstage, Minhaj says that his friend’s parents didn’t want their daughter to take pictures with a brown boy, because they were concerned about what their relatives might think. “I’d eaten off their plates,” Minhaj says. “I’d kissed their daughter. I didn’t know that people could be bigoted even as they were smiling at you.”

But the woman disputed certain facts. She told me that she’d turned down Minhaj, who was then a close friend, in person, days before the dance. Minhaj acknowledged that this was correct, but he said that the two of them had long carried different understandings of her rejection. As a “brown kid in Davis, California,” he said, he’d been conditioned to put his head down and “just take it, and I did.” The “emotional truth” of the story he told onstage was resonant and justified the fabrication of details. “There are so many other kids who have had a similar sort of doorstep experience,” he said.

The woman in question says she has faced threats and doxing because of the claims Minhaj made about her. He has also left out certain information, like the fact that she is engaged to an Indian-American man.

Minhaj is apparently in the running to replace Trevor Noah as the host of the Daily Show. It’s clear from the story that he has no regrets and feels that as long as his stories make a socially-redeeming point then the truth really is secondary. To be clear, I don’t care if comedians are speaking the truth at all times so long as what they’re saying is funny. But it seems to me that being funny wasn’t the point of these concocted stories. These were about showing that Minhaj is a victim of a racist society. The fact that he had to invent or steal those anecdotes from other poeple suggests to me America isn’t quite as bad as he’d like people to believe.

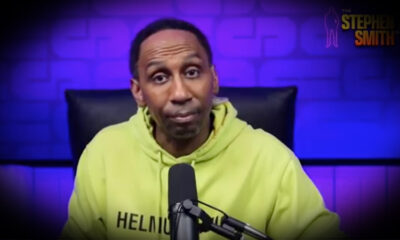

Listen to him tell this heartbreaking and completely made up story about the racists who turned him away from their door.

Read the full article here