Top News

Breitbart Business Digest: Why the Fed Lost Control of the Economy Last Year

The Growth Explosion Almost No One Saw Coming

Why did the economy grow so much faster last year than economists expected?

The answer may be that the Federal Reserve has a lot less influence over business activity than is commonly thought.

Most Wall Street economists—the folks who are well-paid to forecast the economy for the clients of our largest financial institutions—thought we were headed into a recession. And they were wrong. The economy grew 3.1 percent from the fourth quarter of 2022 through the fourth quarter of 2023, including blowout rates of growth of 4.9 percent in the third quarter and 3.3 percent in the fourth quarter.

The Federal Reserve, which employs thousands of economists and financial analysts, did not explicitly project a recession, but the forecasts of its top officials implied we would have one. In December of 2022, the median forecast of Fed officials for growth in the following year was 0.5 percent, a number so low that it amounts to a prediction of a recession sometime during 2023.

It will probably take years for a reliable consensus to develop around why the economics profession and central bankers were so far off when it came to the economy’s growth last year. But because our answers to the question may affect future monetary policy actions and how we look at our economic prospects, it is important to start the investigation immediately.

The Source of Recession Expectations Was Fed Hikes

At the heart of most forecasts for a downturn was the expectation that the rate hikes that had already occurred in 2022 would weigh on the economy in the following year. What’s more, the Fed was expected to hike a few more times in 2023. The Fed describes the state of monetary policy as “restrictive,“ meaning it restricts economic activity. People who worried that the Fed may have gone too far called them “punitive.“

Looking at the growth of 2023, however, it is hard to see what might have been restricted. The unemployment rate in December of 2022 was 3.5 percent. Today, it is 3.7 percent, an almost insignificant climb. The average unemployment rate in 2023 was 3.6 percent—exactly the average in 2022. Businesses and governments—federal, state, and local—kept on adding workers throughout 2023, and layoffs remained extremely low.

The Fed’s median projection at the end of 2022 was for unemployment to rise to 4.6 percent by the end of last year. The range of projections for unemployment ran from four percent to 5.4 percent. Which means that actual unemployment is lower than even the most bullish members of the Fed foresaw.

If the Fed had backed off of rate hikes more than it expected to, this gap would be easy to explain. But the Fed exceeded its expectations. In December 2022, the Fed’s projections showed a median expectation of 5.1 percent for the benchmark fed funds rate for December 2023. Instead, we’re in a range of 5.25 to 5.5 percent, which is the equivalent of 5.4 percent in the language of the Fed projections. In other words, the Fed hiked more than it thought it would.

So, what went wrong? Why was the economy able to grow so much faster than the Fed believed it would?

The Permanent Interest Rate Hypothesis

The answer may be that businesses no longer react to increased rate hikes the way monetary theory leads economists to expect. In theory, when the Fed hikes short-term rates, longer-term rates also rise. This raises the funding costs of business, causing them to invest less in expansion by hiring fewer workers and shrinking capital expenditures. Business plans that might have seemed profitable at a lower rate get shelved because they no longer look as attractive at a higher rate.

An alternative way of looking at it is that since business expansions require risk-taking, raising the risk-free return available to investors and companies “crowds out” private investment. A consumer that can get a five percent return in a money market fund will put less into the stock market, a bank that can park money at the Fed or in Treasuries for five percent lends out less, and a business that can earn a higher return without any risk invests less in risky expansion.

At least, that’s how it works in the economic text books. What we saw last year suggests that it does not work as well in practice. One reason why is that rational business leaders knew that the increase in interest rates was only temporary. Although they might have to borrow more expensively now to finance expansions, they were confident those debts could be refinanced later at lower rates. In a competitive economy, businesses are under pressure to invest to fend off upstarts and rivals, and they do not necessarily pull back on investment because of temporary increases in funding costs. They cannot afford to wait for lower rates to move ahead with their business plans.

When it comes to households, economics has a concept called the “permanent income hypothesis.“ This is the theory that consumers spend money at a level consistent with their expected long-term average income rather than their immediate circumstances. The behavior of businesses in 2023 implies something like a “permanent interest rate hypothesis” is likely to be true. Businesses do not invest based on the current interest rate environment but what they see as the likely average interest rate environment in the longer term.

It may be that temporary interest rate hikes were more effective in the past because businesses were less sure of what to expect from long-term interest rates. An increase from the Fed could imply a permanent or long-lasting move to a higher-rate environment. Similarly, rate cuts would spur more investment as businesses rushed to take advantage of what may be a temporarily good time to borrow. Once long-term rate expectations become “anchored,” temporary departures should be expected to have much smaller impacts.

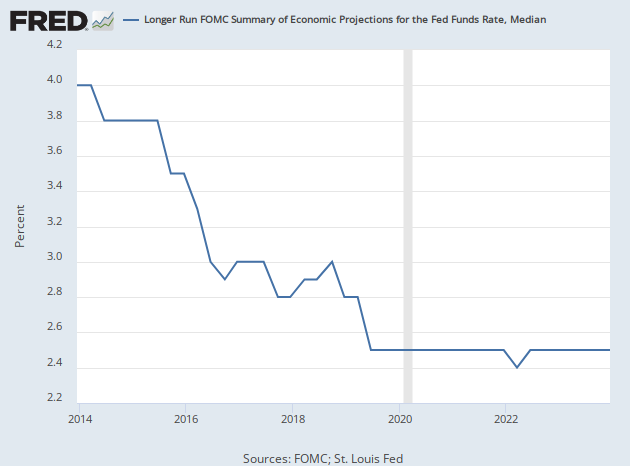

Keep in mind that throughout the pandemic and the inflationary era that followed, the Fed kept its forecast of the fed funds rate over the longer term glued at 2.5 percent. A few years before the pandemic, this used to move around quite a bit. It was as high as three percent back in 2018. But in recent years, it has been almost unmoved, briefly ticking down for just one month in 2022.

This would also help explain two other mysteries of recent economic history: the inversion of the yield curve without a subsequent recession and the failure of corporate bond spreads to widen by very much. If the market had sussed out that rate cuts were coming without a downturn, the yield curve would invert anyway and corporate bond spreads would remain tight.

If the permanent interest rate hypothesis is correct, it would mean that the Federal Reserve’s interest rate policy is a far less powerful tool for controlling macroeconomic conditions than is thought or than it used to be. Going forward, we may have to rely more on things like fiscal policy or other tools long out of favor to keep the economy running smoothly.

Read the full article here