Top News

CPI notes: Biden’s draining off the SPR like a giant with a straw

I just thought I’d point that out.

SPR numbers also out today.. We started draining the SPR under trump. trump sold 57 Million barrels.

Joe has sold 291 Million.

This was supposed to be for emergencies.. but it is keeping the inflation number down. pic.twitter.com/wTBeM9wdcR— Frog Capital (@FrogNews) July 12, 2023

It’s also another reason inflation as read by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) is being held at bay. His pulling that oil out and selling it off is keeping the wraps on oil prices globally, which, in turn, strips that volatility out of the equation for those core prices.

But there IS a bottom to that barrel, and POTATUS has done nothing about refilling what is supposed to be our “emergency” supply, not his personal oily piggy bank.

While the left distracts you with top line CPI including elasticity of energy, CPI minus food and energy increased by 5.6% last month — highest in 30+ years. Food is up 5%.

With #Bidenomics you pay more. pic.twitter.com/2EChOQdADI

— Kyle Lamb (@kylamb8) July 12, 2023

Stand by for when the well runs dry.

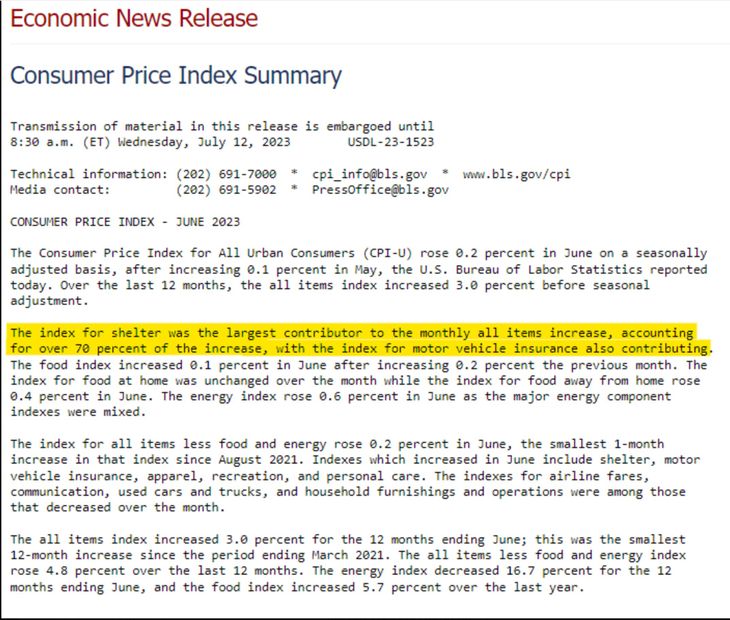

The biggest contributor to the consumer price index was?

Housing.

What are interest rates intended to do to the housing market?

“Crush it” as Frog News says, but with no signs it’s working. It’s still hot as a pistol in many areas, even as mortgage rates top 7%.

Bidenomics doesn’t feel all that terrific and when the hard numbers are put in front of people, i.e. “This cost X in 2021 and now costs +% for Y in 2023,” it just confirms what they know as the tale of the register tape at the grocery store – and the gas station. That it is nowhere near where we once were.

Prices Jan’21 v June ’23… All items +16.6%

Ones that matter most to the everyday consumer:

Food +20%

Gas +52%

Electricity +26%

Vehicle Maint +23%

Vehicle Ins +28%

Interestingly, housing up 15%, less than overall, yet that seems to be Powell’s focus. pic.twitter.com/uZHYgMTi25— Grumpy Old Frog (@GrumpyOldFrog1) July 12, 2023

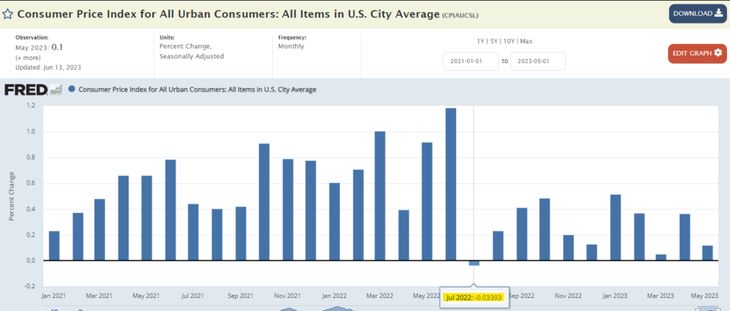

There has actually been only one month – ONE – since Biden took office where the CPI has gone down. Not “been less than the month before,” but gone negative.

Once.

Printing money + tight labor markets + supply chain/price shocks = inflation.

…Inflation optimists (Reifschneider and Wilcox 2022) argued that, even if the new fiscal spending were to drive down unemployment by more than expected, a large burst of inflation was still unlikely, as many studies had concluded that the Phillips curve is quite flat (that is, inflation is relatively insensitive to labor market tightness), and—in light of more than three decades of low inflation in the United States—inflation expectations were likely to remain well anchored.

In contrast, some economists (including one of the authors) argued that wage inflation, and consequently price inflation, could rise much more than predicted by conventional calculations predicated on a flat Phillips curve (Summers, 2021; Blanchard, 2021). Their concerns were that the increase in aggregate demand likely to result from the unprecedentedly large fiscal transfers, together with the cumulative effects of the easing of monetary policy begun in March 2020, could cause more overheating of an already-tight labor market than the optimists expected. An extremely low unemployment rate might in turn cause the Phillips curve to steepen. Moreover, higher and, consequently, more psychologically salient levels of inflation might lead inflation expectations to de-anchor, raising the potential for a wageprice spiral.

The critics’ forecasts of higher inflation would prove to be correct—indeed, even too optimistic—but, in substantial part, the sources of the inflation, at least in its early stages, would prove to be different from those they warned about. The labor market did tighten significantly in 2021 and 2022, as reflected in several indicators, including unsustainably high rates of job creation, an increasing ratio of job openings to unemployed workers, and low levels of quits.2 But, as this paper will show, the behavior of nominal wages in 2021 and 2022 was broadly consistent with the relations the Fed had relied on, and mediumterm inflation expectations rose modestly by some measures but did not de-anchor. Labor market overheating would indeed ultimately prove to be a source of persistent inflation, as the critics had expected, but the traditional wage Phillips curve mechanism was not the main event, at least not until recently.

In retrospect, the failure to forecast the inflation burst reflected in large part the fact that, in focusing on the labor market, both the Fed and its critics underestimated the inflationary potential of developments in goods markets, that is, from increases in prices given wages. The shocks to prices came from several sources. First, like other forecasters (including participants in commodity futures markets), most economists did not anticipate either the magnitude or the duration of the rise in commodity prices that began in 2021. Beyond the more-familiar (but unexpectedly large and sustained) shocks to food and energy prices, the pandemic itself led to unusual distortions in key product markets, such as those for new and used vehicles. Strong aggregate demand and shifts in the composition of consumer spending (e.g., from services to durable goods) during the pandemic combined with constraints on supply in some sectors to create shortages and sectoral price increases not offset by decreases in other sectors (Guerrieri et al., 2022; di Giovanni et al., 2023). These sectoral mismatches between demand and supply proved more intractable and longer-lasting than many had expected. Together, these shocks to prices given wages would prove to be the critical triggers of the rise in inflation

Those labor markets stayed tight because the printed government money kept people home.

In an aside, as Bernanke and Co. mention vehicle prices as part of the price “shocks” contributing to inflation, may I remind the gentle viewer of the 677,081 mostly operational vehicles the Obama administration pulled off the road and summarily executed during Cash for Clunkers? If you don’t think for two seconds taking almost three quarters of a million mostly viable, affordable, second-hand vehicles off the road wasn’t a huge factor in what we’re facing now as far as inflationary pressures, I have a watch I’d like to sell you. It wasn’t long after that when Midwest floods and all sorts of natural disasters hit, and a rental car couldn’t be found for love nor money.

Nor could a secondhand vehicle to replace your flooded one, less mind a reasonably priced used car.

And here we are.

So that’s my twelve cents (was ten in 2021) addition to Ed’s excellent reporting on the numbers when they came out this morning.

Read the full article here