Top News

Mansour: The Spirit of 1776—How 13 Rebellious Colonies Declared Their Independence

So many Americans today believe that our political differences have become so intractable and our discourse so toxic that our very democracy is at risk. What they fail to realize is that our political differences have always seemed insurmountable, and our democracy was never easy.

The story of the birth of our nation by Declaration in July of 1776 is a story of disagreements, debates, compromises, and moral courage. It’s a story of a group of rebellious Englishmen who—despite their many differences—could agree on one thing: they wanted to live free.

“The First Man in House”

If there was one quintessential figure among the delegates from the 13 colonies assembled in Philadelphia for the Continental Congress, it was John Adams from the Massachusetts delegation.

Benjamin Rush of Philadelphia would later say that “every member of Congress in 1776 acknowledged Adams to be the first man in the House.” Thomas Jefferson called Adams “our colossus on the floor.”

Adams, a gifted lawyer and floor debater, had the foresight and the courage to see that the only way forward was for the Continental Congress to declare its independence and break free from the British crown once and for all. He and all the other delegates from New England were for liberty from the start because they were already at war. The “shot heard ‘round the world” at Lexington and Concord was fired by the patriots of the New England who were bearing the brunt of British military occupation.

Battle of Lexington on April 19, 1775, painting by William Barnes Wollen (National Army Museum)

Massachusetts was at war before all of the other colonies. Boston was occupied by British troops. While Adams was at the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia, his wife, Abigail, could hear the thunder of the bombardment of Bunker Hill from their farm in Braintree, Massachusetts.

So, the question of liberty wasn’t an intellectual discussion for the men of New England. It was a matter of life and death. And, as they saw it, the only way they could guarantee their liberty was by declaring their independence from the mother country and its occupying army.

Portraits of John and Abigail Adams in 1766 by Benjamin Blyth. (Wikimedia Commons)

“The Revolution Was in the Minds and Hearts of the People”

There was talk of independence at the Continental Congress in 1775, but only talk. Declaring independence was a massive, unprecedented, and irrevocable act. It was high treason punishable by death. The men of New England, who were dying already, understood this. But how could they convince the other colonies to join them?

If a decision on independence were forced on the Continental Congress too soon, the result could be disastrous because independence would be voted down by the other delegates. Adams knew that any declaration of independence had to be made unanimously. All 13 colonies must unite to break free together for any hope of victory.

But there was no unanimity in 1775. The Continental Congress was about equally divided into three groups. First, there were the Tories who basically opposed independence. Then there were those who were too cautious or too timid to take a position one way or another. And finally, there were the patriots—mostly New Englanders—who wanted independence as soon as possible.

In 1775, the voices for independence were in the minority. In fact, the delegates of six colonies—New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, and South Carolina—were under specific instructions not to vote for independence under any circumstances.

In the middle colonies and in parts of the South, a large number of people had no wish at all to separate from Great Britain. That was also the attitude in Philadelphia itself, which had a strong Tory contingent and many staunch pacifist Quakers who wanted to avoid war at all costs. In their eyes, George III was a good king and the New Englanders were hotheads and rebel rousers.

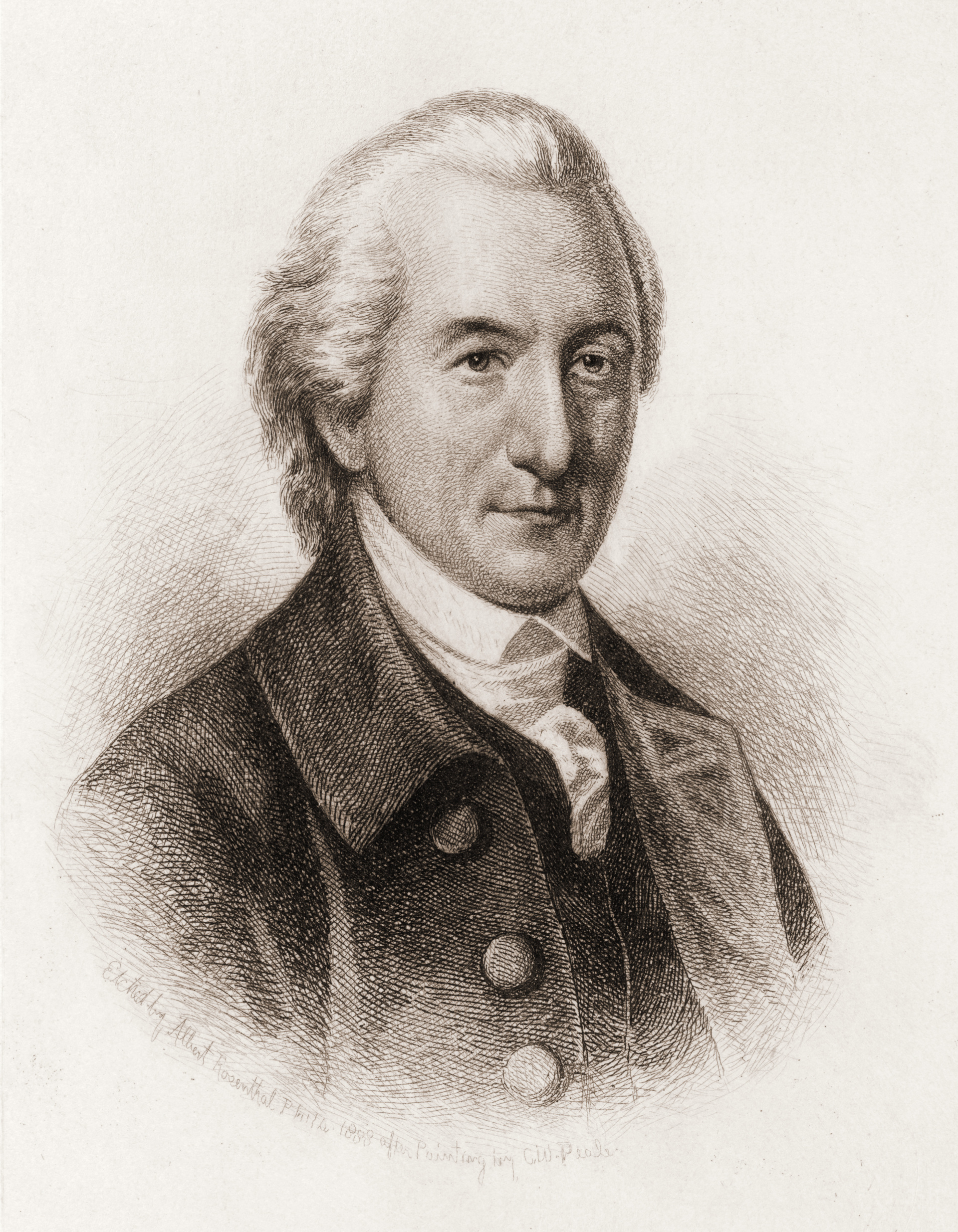

John Dickinson of Pennsylvania. (Getty Images)

But these sentiments were gradually changing. In Virginia, on New Year’s Day 1776, the royal governor ordered the bombardment of Norfolk. Suddenly, the delegates from Virginia were moving to the side of independence—and that was no small thing because Virginia was the wealthiest and oldest of the colonies.

And then there was Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania who was also on Adams’ side, but he had no interest in the floor debate. He left that to Adams. He never tried to take the lead. Instead, he calmly observed and offered advice behind the scenes.

In fact, it was another member of the Pennsylvania delegation—John Dickinson—who was the clear leader of the faction against independence. It was Dickinson’s idea to send King George III the “Olive Branch Petition” of July 8, 1775, which humbly beseeched the king to restore peace.

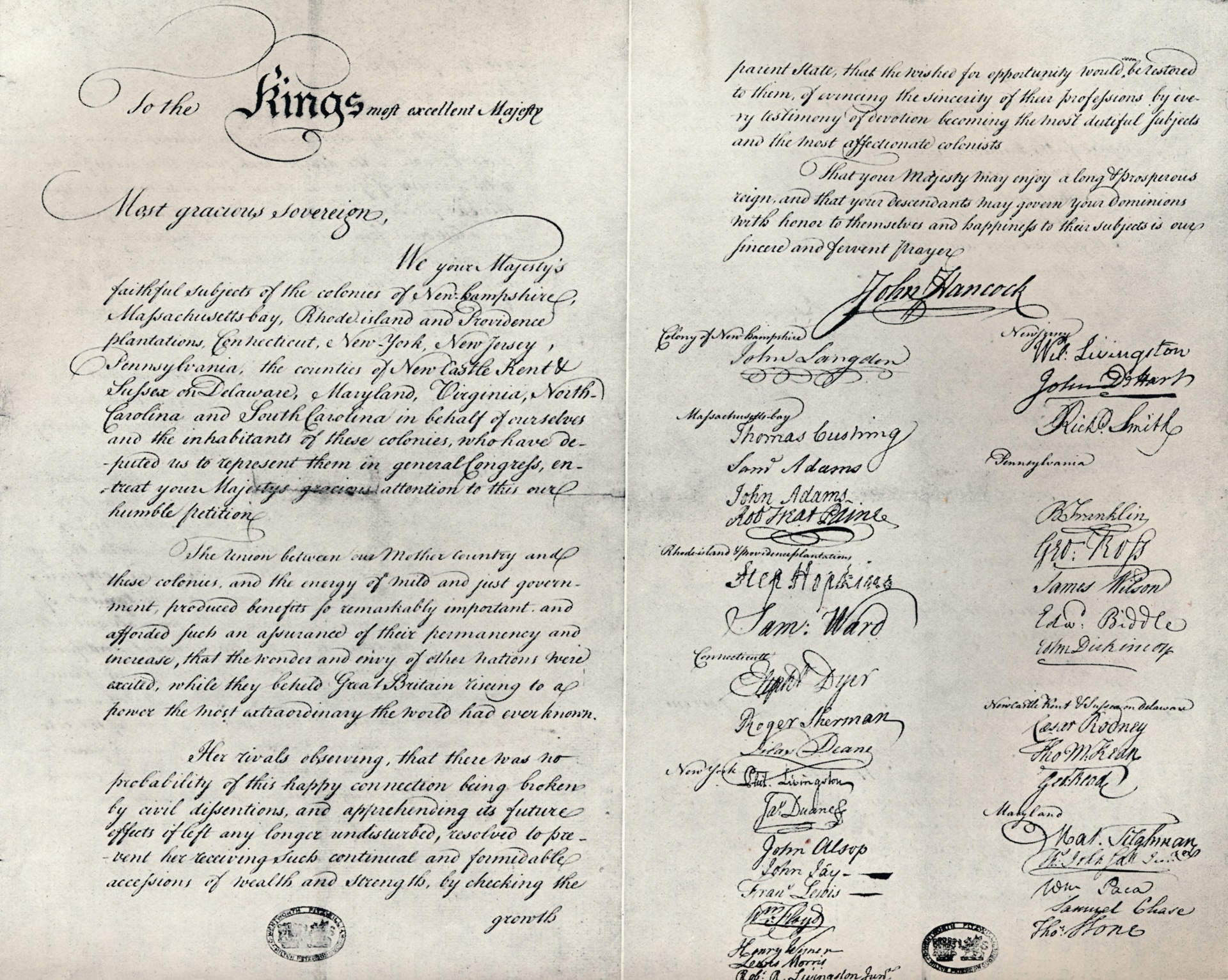

The Fitzwilliam copy of the Olive Branch Petition, 1775 sent to King George III. (The Print Collector/Getty Images)

This petition outraged John Adams. The very idea that they would send this groveling supplication to King George after what the British had done at Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill was appalling and idiotic to him.

Adams had seen the carnage the British had wrought in Massachusetts. He couldn’t believe anyone would be so naive as to think that the British would go home and leave them in peace if asked nicely. Adams would write: “Powder and artillery are the most efficacious, sure and infallible conciliatory measures we can adopt.”

But, still, the petition was sent to the King, and of course George III refused to even look at it, and instead he proclaimed the colonies in a state of rebellion. This meant there was no going back.

Portrait of King George III by Johan Zoffany, 1771. (Wikimedia Commons)

By Spring of 1776, the idea of independence was being being talked about openly. And it was helped in large part by Thomas Paine’s revolutionary pamphlet Common Sense. As John Adams would later write, “The Revolution was in the minds and hearts of the people.”

Now the delegates of three southern colonies—South Carolina, Georgia, and North Carolina—received instructions freeing them to vote for independence.

But even among the opposition, there was growing agreement on the need for unanimity, as Benjamin Franklin said, “We must hang together or separately.”

“Free and Independent States”

By the end of May 1776, General Washington arrived at the Continental Congress to report on the situation in New York, where a British attack was expected any day. The delegates were informed that King George III had hired 17,000 German Hessian troops to fight in America. So, their own king was sending foreign mercenaries to attack them.

Then news came that the Virginians had resolved unanimously to instruct their delegation at Philadelphia “to declare the United Colonies free and independent states.”

That was the turning point. This was the moment the New Englanders had been waiting for. Once Virginians broke for liberty, the fight was on.

On Friday, June 7, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia rose to speak, saying:

“Resolved That these United Colonies are, and of a right ought to be, free and independent states, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the state of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.”

Adams immediately seconded the motion. But then the real debate began.

Dickinson and his faction demanded a cooling off. They wanted “the voice of the people” to be heard before they proceeded with any vote. Of course, Adams argued that the people were already behind independence and were just waiting for Congress to lead them.

But again, they proceeded with caution. So, on June 10, the decision was made to delay the final vote until July 1 so that all the delegates from the middle colonies could send for new instructions from home on whether to vote for independence.

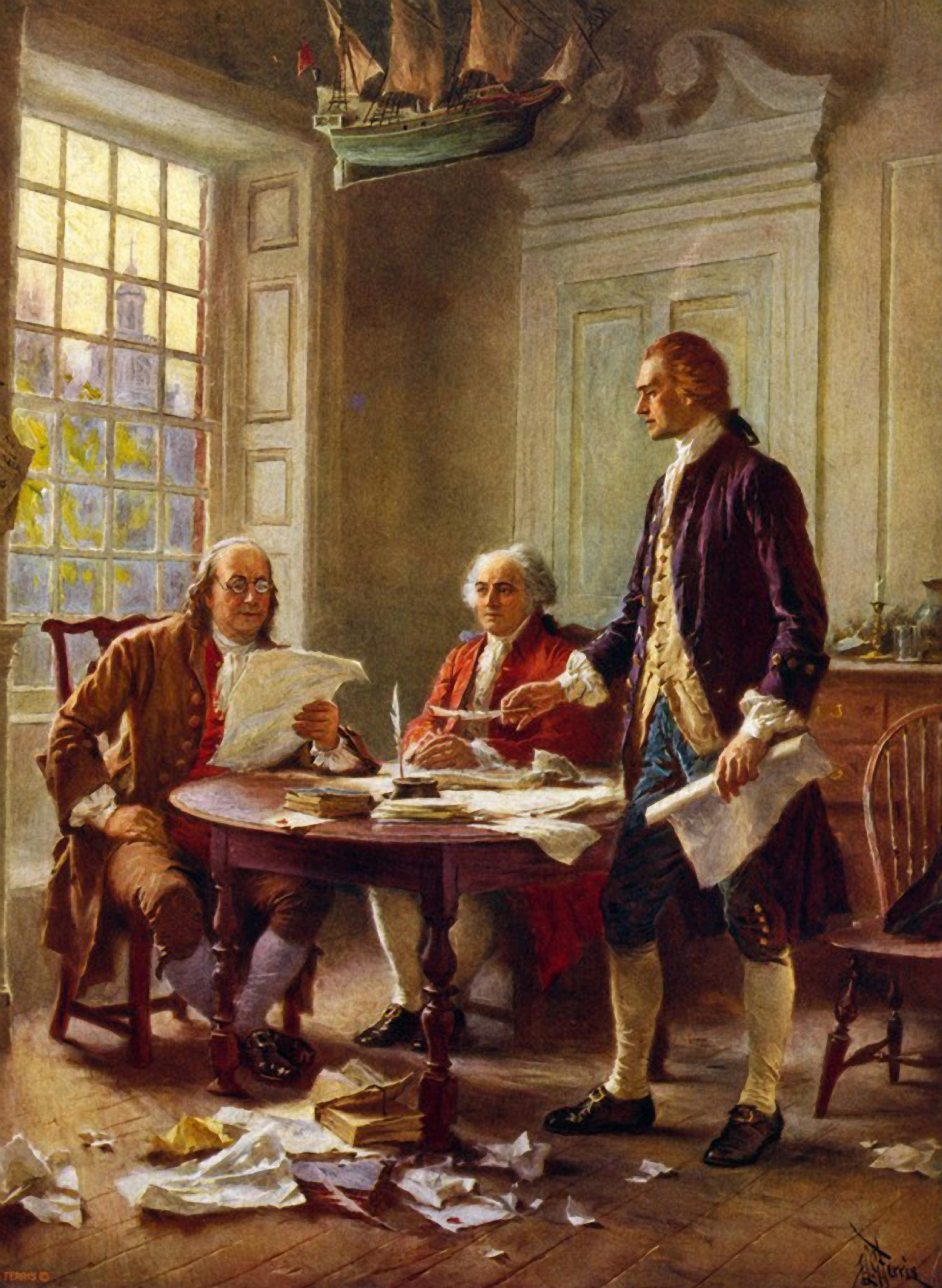

In the meantime, a committee was appointed with the task of preparing a document that would be a declaration of independence, and Thomas Jefferson of Virginia was given the job to write it.

“Writing the Declaration of Independence, 1776” depicting Benjamin Franklin, left, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, standing, meeting in Philadelphia to study a draft of the document. Painting by J.L.G. Ferris. (Getty Images)

“Objects of the Most Stupendous Magnitude”

The Congress reconvened on Monday, July 1, 1776. It was hot and humid in Philadelphia that day. A full-scale summer storm was coming.

At ten o’clock, with the doors closed, John Hancock sounded the gavel. Richard Henry Lee’s prior motion calling for independence was again read aloud.

Immediately, John Dickinson stood to be heard. One last time, he warned against the “premature” separation from Britain. He spoke eloquently and passionately. He argued that to declare independence would be “to brave the storm in a skiff made of paper.”

When he sat down, there was silent except for the rain that had begun spattering against the windows. No one spoke, no one rose to answer him, everyone felt the weight of the moment and of the decision.

Then Adams stood up to make the case for liberty.

Independence Hall, Philadelphia, where the Continental Congress convened. (Wikimedia Commons)

He began by saying that he wished he had the gifts of the ancient orators of Greece and Rome because he was certain that none of them had ever confronted a question of greater importance to the history of mankind.

Outside, the wind picked up. The storm started to strike thunder and lightning, with rain pelting against the windows.

Inside, Adams spoke logical and with incredible passion. He offered a hopeful vision of the future before them—of the birth of a great new nation. He was mindful that this was an immense moment in human history, when, for the the first time, a free people were deciding to be self-governed.

We don’t have his exact words because he never gave prepared remarks. But we know his sentiments from the words he wrote to a friend at that time:

“Objects of the most stupendous magnitude, measures in which the lives and liberties of millions, born and unborn are most essentially interested, are now before us. We are in the very midst of revolution, the most complete, unexpected, and remarkable of any in the history of the world.”

Even though we have no transcription of his remarks, we have the recollections of the people who were there. And there was no question in anyone’s minds that Adams’ words that day were the most powerful and important speech ever delivered in the Continental Congress.

Jefferson would write that Adams spoke “with a power of thought and expression that moved us from our seats.”

Years afterward, Adams would say he had been “‘carried out in spirit,’ as enthusiastic preachers sometimes express themselves.”

Richard Stockton, the delegate from New Jersey, said that Adams was “the Atlas” of the hour, “the man to whom the country is most indebted for the great measure of independency…. He it was who sustained the debate, and by the force of his reasoning demonstrated not only the justice, but the expediency of the measure.”

The debate continued that day. More were persuaded. Ultimately the final vote was postponed again until the next day, July 2, for the sake of unanimity, as they were trying to persuade the final holdouts from South Carolina. And they were waiting for Caesar Rodney of Delaware to arrive.

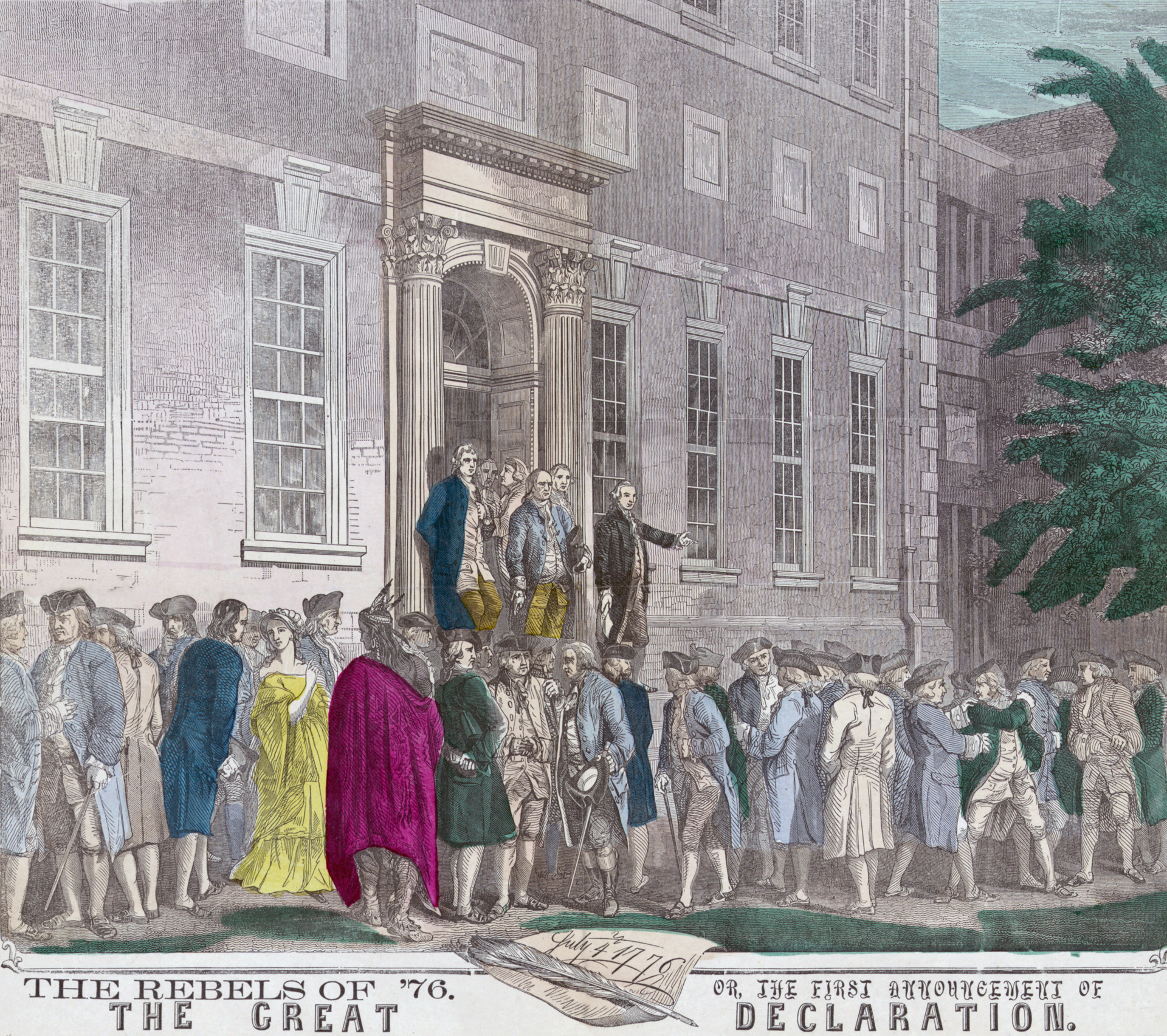

Delegates at the Second Continental Congress voting on the Declaration of Independence. (Wikimedia Commons)

“The Most Memorable Epocha in the History of America”

On Tuesday, July 2, they reconvened to vote on the question of independence.

Just as the doors to Congress were about to be closed that morning to start the session, Caesar Rodney made his dramatic entrance. He had ridden eighty miles through the night to be there in time to cast his vote for independence.

John Dickinson and Robert Morris of the Pennsylvania Delegation had voluntarily absented themselves that day because, even though they refused to vote for independence, they understood the need for unanimity. So, they stayed away and that allowed the remaining Pennsylvania delegates to vote for independence.

New York continued to abstain, but South Carolina finally joined the majority to make the decision unanimous in the sense that no colony stood opposed.

So, it was done. The break was made. On July 2, 1776, in Philadelphia, the American colonies declared independence.

That night John Adams would write to his wife Abigail:

“The second day of July 1776 will be the most memorable epocha in the history of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated by succeeding generations as the great anniversary festival. It ought to be commemorated as the Day of Deliverance by solemn acts of devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires, and illuminations from one end of this continent to the other from this time forward forever more.”

Signing the Declaration of Independence. (Getty Images)

“We Hold These Truths to Be Self-Evident”

The next day, they reconvened to deliberate on the wording of the Declaration of Independence.

Thomas Jefferson sat silently while they changed his wording and even cut out about a quarter of what he wrote.

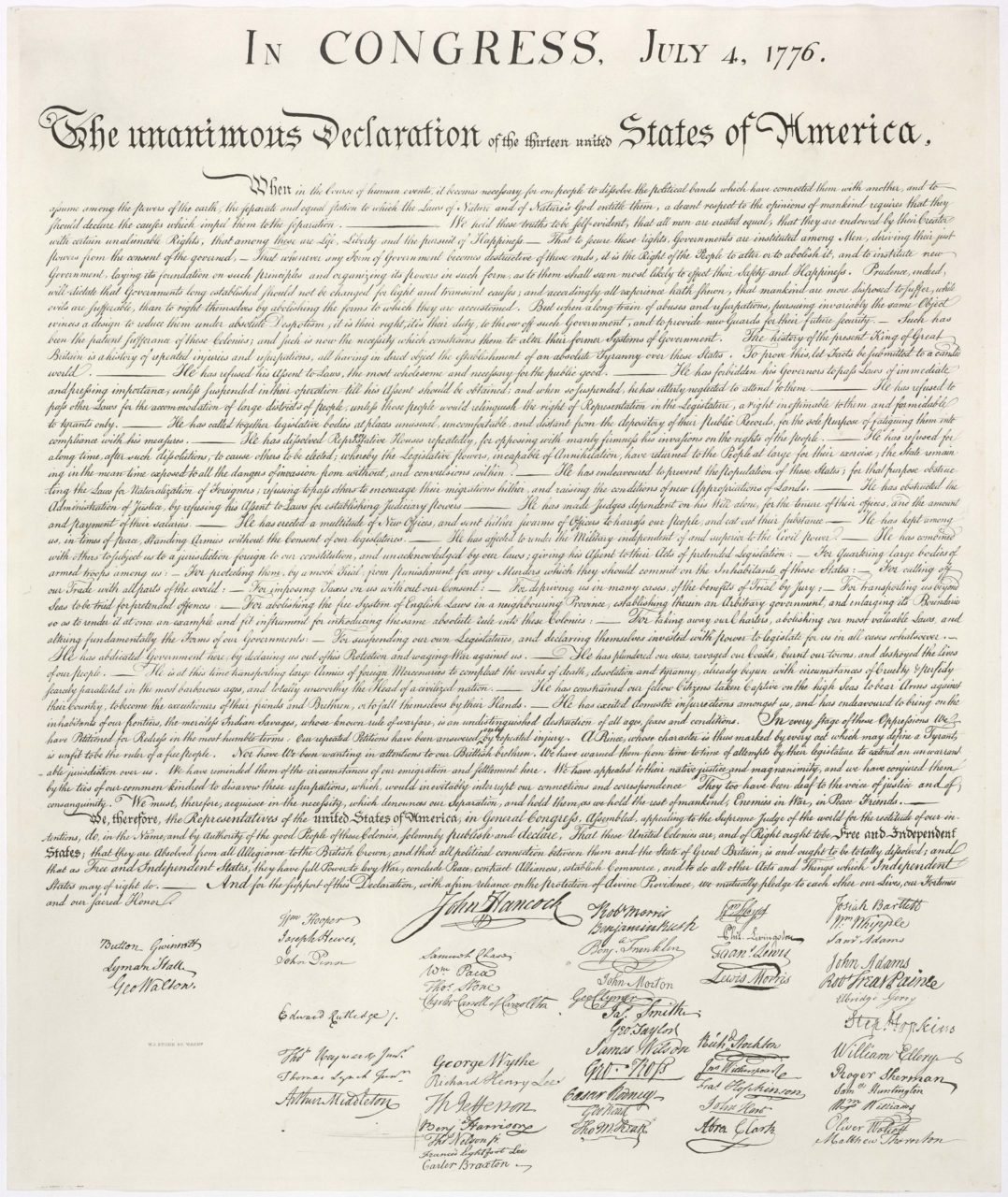

Despite the changes, one passage rang out like poetry that lit a fire into men’s hearts around the world, even to this day. It was a passage that encapsulated the principles that Jefferson would later characterize as “the Spirit of ’76”:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. That to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

One final thing they all agreed on was to add a key phrase to Jefferson’s concluding line that would commend their entire endeavor to God’s protection.

So, it would read:

“And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor.”

And, thus, our country was born by Declaration in Philadelphia in July 1776.

Every generation of Americans who bind themselves to the sentiments espoused in that document is a part of that Spirit of 1776.

On July 4, 1776 members of the Second Continental Congress leave Philadelphia’s Independence Hall after adopting the Declaration of Independence. (Getty Images)

Read the full article here